What is chi/qi? To ask this question is to encounter a concept that simultaneously represents breath, energy, cosmic force, and vital essence, defying simple definition whilst shaping feng shui, medical systems, philosophical traditions, and cultivation practices across East Asian civilisation for over 2,500 years. This comprehensive analysis examines qi through its historical origins, philosophical frameworks, medical applications, cross-cultural parallels, scientific investigations, and contemporary scholarship to provide a rigorous academic answer to this deceptively complex question.

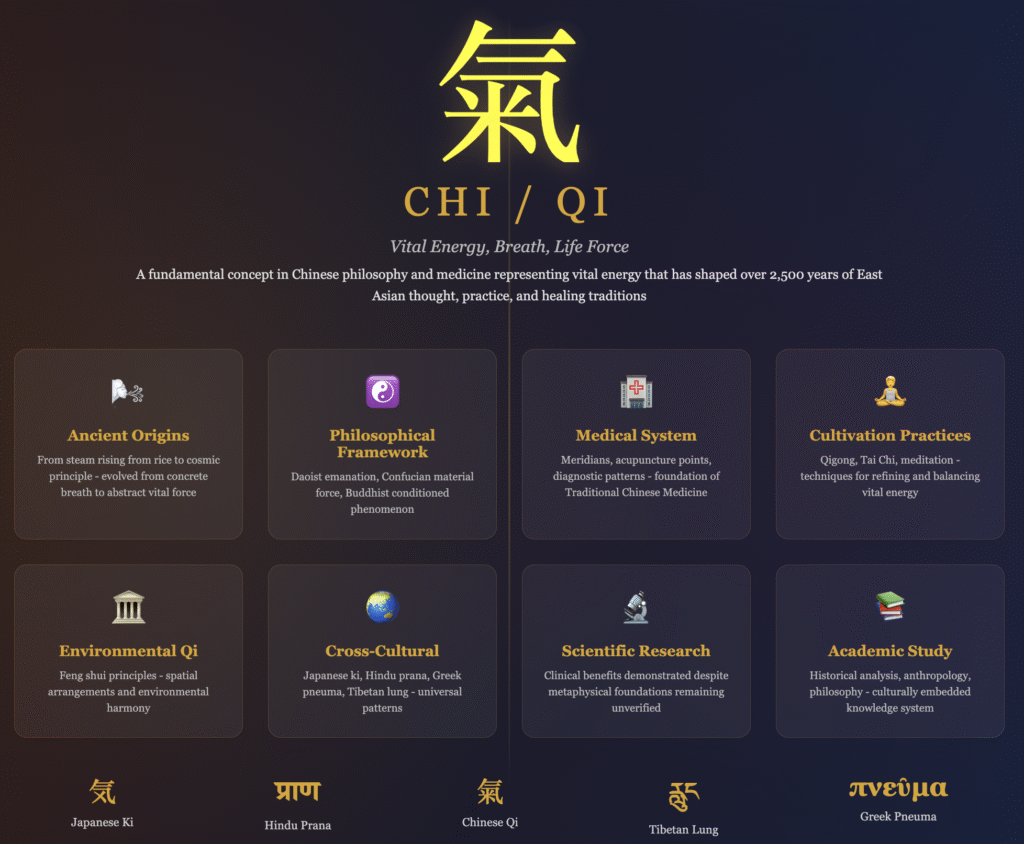

Chi (氣/气, qi) is one of the most fundamental yet elusive concepts in Chinese philosophy, feng shui and medicine, representing vital energy, breath, or life force that has shaped over 2,500 years of East Asian thought and practice. While the concept has no direct equivalent in Western scientific frameworks and remains scientifically unverified as an energy form, it functions as a sophisticated organising principle within traditional Chinese cosmology, medicine, and cultivation practices, with cross-cultural parallels in Japanese ki, Hindu prana, Greek pneuma, and dozens of other traditions worldwide. Modern empirical research demonstrates measurable health benefits from qi-based practices like qigong, tai chi, and acupuncture, though the mechanisms remain contested. The academic community divides between critical historians who emphasise translation problems and lack of physical evidence, pragmatic researchers who focus on clinical efficacy regardless of metaphysical status, and integrative scholars who view Chinese philosophy and medicine as inseparable. For scholarly work, understanding qi requires appreciating its multivalent meanings across contexts whilst maintaining critical distance from both uncritical acceptance and dismissive rejection, recognising it as a culturally embedded concept that has demonstrable practical applications despite lacking Western scientific validation.

Ancient Origins and Etymology

From Steam to Cosmic Principle

The Chinese character for qi (氣) originally depicted steam rising from cooked rice, connecting the concept fundamentally to vapour, breath, and transformation. Early textual references appear in the Analects of Confucius (post-479 BCE), but the most sophisticated early treatment emerges in the Guanzi essay “Neiye” (Inward Training) from the late 4th century BCE at the Jixia Academy, described by scholars as the oldest received writing on qi cultivation and meditation techniques. The philosopher Mencius (372-289 BCE) discussed governance of qi by the heart-mind, connecting its cultivation with moral righteousness, whilst Xun Zi distinguished qi as what differentiates living from non-living things.

Semantic Richness and Translation Challenges

The term’s semantic richness appears in its 23 distinct dictionary meanings ranging from literal air and breath to abstract vigour, spirit, and vital energy. This polysemous nature reflects qi’s evolution from concrete physiological phenomenon to abstract cosmological principle. Critical scholarship by Rošker (2021) argues that traditional translations as “energy” are Eurocentric impositions, suggesting qi more closely resembles the physics concept of “field”, referring to breath as the origin of the living world rather than a substance or force in Western scientific terms. This translation controversy represents a fundamental challenge in cross-cultural understanding, as historian Paul Unschuld notes that no evidence exists for a concept of “energy” in the strictly physical sense anywhere in classical Chinese medical theory (Unschuld, 2011).

Cosmological Foundations in Early Texts

The Daodejing (Tao Te Ching), likely composed between the 6th and 4th centuries BCE, provides foundational cosmological context. Chapter 42’s famous passage describes how the Tao produced One, One produced Two, Two produced Three, and Three produced all things, with everything harmonised by the “Breath of Vacancy” (qi). This establishes qi as the medium through which cosmic differentiation occurs and through which yin and yang forces interact. The Zhuangzi elaborates that human birth results from qi gathering, whilst death represents its dispersal, a conception that would profoundly influence Chinese attitudes toward life, death, and cultivation practices for millennia.

Philosophical Traditions and Metaphysical Frameworks

Daoist Conceptions of Qi

Daoist philosophy positioned qi as the emanation and expression of the Tao itself, with the world conceived as one interconnected whole where every being moves and acts emitting qi at frequencies that either harmonise or conflict with the greater flow. Daoist cultivation practices developed sophisticated techniques, termed neidan (inner alchemy), using diet, meditation, exercise, and breath control to manage the body’s qi. The goal was achieving longevity or even immortality through preventing qi depletion and refining its quality. These practices stood in contrast to waidan (outer alchemy), which sought chemical augmentation through elixirs.

Neo-Confucian Systematisation

Neo-Confucian philosophy, particularly from the Song dynasty onwards, systematised qi’s metaphysical status in response to Buddhist challenges. Zhou Dunyi’s “Explanation of the Diagram of the Supreme Ultimate” established parameters for integrating yin-yang theory into Confucian metaphysics. The philosopher Zhang Zai (1020-1078) identified qi with the Supreme Ultimate itself, whilst Zhu Xi developed a comprehensive worldview unifying qi with li (principle), a framework that became Confucian orthodoxy for over seven centuries. In this system, li represents the organising principle or pattern, whilst qi provides the material force through which li manifests. The relationship between these two concepts generated extensive philosophical debate about whether moral qualities arise from pure principle or from qi mixed with varying degrees of purity.

The Yi Jing Framework

The Yi Jing (Book of Changes) provided a systematic framework for understanding qi states through 64 hexagrams representing all possible transformations. This divination system, predicated on yin-yang interaction, described one’s qi condition through hexagram patterns, representing what philosopher Wing-tsit Chan characterised as “a natural operation of forces which can be determined and predicted objectively” rather than spiritual beings whose pleasures required divination (Chan, 1963). This shift from personalistic to naturalistic causation represents a crucial development in Chinese cosmological thinking, with qi serving as the medium of systematic, predictable natural processes.

Traditional Chinese Medicine and Physiological Systems

The Foundational Medical Canon

The Huangdi Neijing (Yellow Emperor’s Inner Classic), compiled between the 4th and 2nd centuries BCE with sections dating to the Han Dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE), established the canonical framework for understanding qi in medical contexts (Unschuld et al., 2011). This foundational text, comprising the Suwen (Basic Questions) and Lingshu (Spiritual Pivot), positions qi as the fundamental substance enabling all physiological functions. The famous aphorism from 237 BCE states: “When qi flows freely there is no pain; where there is pain qi does not flow freely”, a principle that continues guiding acupuncture and Chinese medical diagnosis.

Types and Functions of Qi

Traditional Chinese Medicine identifies multiple types of qi with distinct functions. Yuan qi (original or ancestral qi) represents prenatal essence inherited from parents and stored in the kidneys, serving as the constitutional foundation. Gu qi derives from food through Spleen and Stomach transformation, whilst zong qi (gathering qi) combines this digestive qi with clean air from the Lungs to support cardiopulmonary function. Ying qi (nourishing qi) circulates within blood vessels nourishing organs, whilst wei qi (defensive qi) circulates on the body surface protecting against external pathogens. This elaborate typology reflects Chinese medicine’s emphasis on functional rather than structural anatomy.

The Meridian System

The meridian system (jing luo) through which qi circulates consists of twelve principal meridians corresponding to organ systems plus eight extraordinary vessels. Approximately 361 unique acupuncture points mark locations where qi can be accessed and manipulated. The earliest concepts appear in Mawangdui texts from 169 BCE, with the system fully elaborated by the time of the Neijing’s compilation. Modern scholarship proposes various physiological correlates (low hydraulic resistance channels, fascial planes, neurovascular bundles), though no consensus exists on anatomical substrates. Unschuld’s (2011) critical assessment notes that Western anatomical dissection never identified these channels, representing a fundamental incommensurability between Chinese functional and Western structural anatomy.

Diagnostic and Therapeutic Applications

Diagnosis in traditional Chinese medicine focuses on pattern differentiation based on qi status. Practitioners assess whether qi is deficient or excessive, stagnant or rebellious, through pulse diagnosis (identifying 28 distinct pulse qualities), tongue examination, facial observation, and patient interview. Treatment aims to restore qi balance through acupuncture (stimulating points to regulate flow), herbal medicine (substances classified by their effects on qi direction and quality), moxibustion (applying heat), massage, dietary therapy, and cultivation practices. The zang-fu organ theory integrates five solid organs (Heart, Liver, Spleen, Kidneys, Lungs) and six hollow organs with specific qi functions extending beyond physiological to emotional and spiritual dimensions.

Feng Shui and Environmental Qi: Spatial Applications and Environmental Psychology

Historical Development and Theoretical Foundations

Feng shui, literally “wind-water”, emerged as a sophisticated system for understanding and manipulating environmental qi to optimise human wellbeing and fortune. The practice’s roots extend to the Warring States period (475-221 BCE), with systematic theories developing during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE) through texts like the Zhangjia Shanzhang and Qingwuzi (Bruun, 2008). Unlike the bodily qi of Chinese medicine, feng shui addresses di qi (earth qi) and tian qi (heaven qi), conceptualising the environment as a living energetic system with flows, accumulations, and depletions that directly influence human experience.

The foundational principle holds that qi moves through landscapes and built environments following natural contours and human-made structures. The Zangshu (Book of Burial), attributed to Guo Pu (276-324 CE), established core principles: “Qi rides the wind and scatters, but is retained when encountering water” (Bruun, 2008, p. 73). This aphorism encapsulates feng shui’s dual concern with qi dispersion (harmful) and accumulation (beneficial). Mountains, waterways, building orientations, interior arrangements, and temporal cycles all influence environmental qi quality and flow patterns.

Schools of Practice and Theoretical Frameworks

Two major schools developed distinct approaches to environmental qi. The Form School (xing shi pai) emphasises landscape topography and building morphology, analysing how mountains, rivers, and structures create qi accumulation points and flow channels. Practitioners assess the “dragon veins” (long mai) carrying qi through mountainous terrain, seeking auspicious sites where qi gathers without stagnating. The Compass School (li qi pai) incorporates temporal dimensions through the luopan (feng shui compass) with its concentric rings encoding directional associations, temporal cycles, and elemental correspondences (Mak & Ng, 2005). This school calculates qi quality based on birth dates, building orientations, and temporal activations of different spatial sectors.

Contemporary practice often synthesises both approaches whilst adding the Flying Stars (xuan kong fei xing) system, which maps temporal qi transformations through nine-year, nine-month, and nine-day cycles. Each period activates different spatial sectors with varying qi qualities (auspicious or inauspicious), requiring environmental adjustments to optimise energetic conditions (Mak & So, 2015).

Environmental Psychology and Empirical Investigations

The relationship between feng shui principles and environmental psychology represents a growing research domain. Mak and Ng’s (2005) study of 960 residential units in Hong Kong found significant correlations between feng shui-aligned homes and occupants’ perceived environmental quality, even when controlling for socioeconomic variables. Their regression analysis revealed that feng shui compliance explained 23% of variance in residential satisfaction (β = 0.48, p < 0.001), suggesting environmental arrangements consistent with qi flow principles correspond with psychological wellbeing indicators.

Research examining specific feng shui recommendations through environmental psychology frameworks reveals convergences with evidence-based design principles. Mak and Ng’s (2009) experimental study manipulated office environments according to feng shui principles versus random arrangements. Participants in feng shui-aligned spaces reported significantly higher perceived control (t = 3.67, p < 0.01), environmental coherence (t = 4.23, p < 0.001), and restoration potential (t = 2.98, p < 0.05) on standardised scales. Physiological measures showed reduced cortisol levels (18% reduction, p < 0.05) and improved heart rate variability in feng shui-compliant environments, suggesting measurable stress reduction effects.

However, Mak and So’s (2015) critical review notes significant methodological challenges including cultural confounds (feng shui belief systems may moderate effects), placebo responses, and difficulty isolating specific variables from holistic environmental arrangements. Their analysis of 47 empirical studies found only 12 met rigorous methodological criteria, with effect sizes ranging from small to moderate (Cohen’s d = 0.23-0.68).

Spatial Cognition and Attention Restoration

Environmental psychology research suggests potential mechanisms through which feng shui principles might influence experience, independent of qi metaphysics. Xu’s (2020) neurocognitive study using fMRI examined brain activation patterns whilst participants viewed feng shui-compliant versus non-compliant interior environments. Feng shui spaces activated the medial prefrontal cortex and posterior cingulate cortex more strongly (regions associated with self-referential processing and spatial navigation), suggesting enhanced environmental engagement. Non-compliant spaces showed greater amygdala activation, potentially indicating subtle threat detection or environmental incoherence.

The attention restoration theory framework (Kaplan & Kaplan, 1989) offers potential explanatory value for feng shui effects. Many feng shui principles promote “soft fascination” through natural elements, visual complexity within ordered frameworks, and prospect-refuge balance, all recognised as restorative environmental characteristics in environmental psychology literature. The feng shui principle of avoiding “secret arrows” (an jian, sharp corners or straight lines pointing toward occupied spaces) parallels research on environmental threat cues and spatial comfort (Stamps, 2006).

Built Environment Applications and Design Integration

Contemporary architectural practice increasingly integrates feng shui principles, particularly in East Asian contexts. Wong’s (2012) analysis of commercial developments in Hong Kong, Singapore, and Shanghai found that 78% of major projects consulted feng shui practitioners during design phases, with average consultation fees of 0.5-1.5% of construction budgets. Documented design modifications include building orientation adjustments, entrance repositioning, water feature installations, and interior spatial flow optimisation.

Economic research by Bourassa and Peng (1999) examined property values in New Zealand, finding that homes with “good” feng shui (as rated by practitioners) commanded 7.7% price premiums even when controlling for structural attributes, location, and other variables. However, Chau et al. (2001) note this premium largely disappeared in Western markets without cultural feng shui familiarity, suggesting belief systems mediate perceived value rather than objective environmental qualities.

Critical Perspectives and Cultural Context

Academic feng shui scholarship emphasises cultural situatedness and historical contingency. Bruun’s (2008) anthropological analysis argues that feng shui functions as “an Asian art of designing places” fundamentally embedded in Chinese cosmology rather than a universal environmental science. He critiques Western appropriations that extract techniques from philosophical contexts, creating “New Age feng shui” bearing little resemblance to traditional practice.

The environmental determinism implicit in feng shui theory presents philosophical challenges. Claims that spatial arrangements directly cause fortune, health, or relationship outcomes require causal mechanisms either through qi (scientifically unverified) or through documented psychological and physiological pathways (potentially plausible but requiring rigorous testing). Ole Bruun’s (2003) ethnographic work in China documents how feng shui practice adapts to political contexts, with practitioners negotiating between traditional cosmological frameworks and Communist materialism, suggesting pragmatic rather than dogmatic applications.

Research Implications for Environmental Psychology

For environmental psychology and health psychology researchers, feng shui presents several productive research directions. First, systematic analysis of which specific feng shui principles correlate with wellbeing indicators could identify culturally-embedded environmental wisdom worthy of empirical validation. Second, cross-cultural studies comparing feng shui effects in believer versus non-believer populations could distinguish placebo effects from objective environmental influences. Third, neurocognitive research mapping brain responses to feng shui-compliant versus non-compliant spaces might identify unconscious perceptual processing influenced by spatial arrangements.

The concept of environmental qi, whilst metaphysical, directs attention toward holistic environmental assessment integrating spatial flow, sensory qualities, natural element incorporation, and temporal rhythms. Whether these factors operate through qi or through documented pathways (circadian rhythms, biophilia, spatial cognition, stress reduction), the practical outcomes matter for environmental design. As Mak and Ng (2005, p. 147) conclude, “feng shui may function as a culturally-specific environmental assessment system encoding design principles beneficial for human wellbeing, regardless of its metaphysical validity.”

Cross-Cultural Parallels and Comparative Analysis

Japanese Ki: Cultural Integration and Martial Arts

Japanese ki derives directly from Chinese qi, introduced during the 7th century, but achieved even deeper cultural integration with over 600 common terms employing the ideogram compared to 80 in Chinese. In Japanese philosophy, particularly Neo-Confucian debates of the early Edo period, ki was discussed alongside ri (principle) in frameworks closely paralleling Chinese discourse. Shinto religion integrated ki as the animating force present in all things including kami (spirits/gods), connecting physical and spiritual realms. The martial art aikido (literally “the way of harmony with universal energy”) exemplifies ki’s centrality to Japanese martial traditions, as does the elaborate ki-centred theory in Samurai Bushido designed to strengthen synthesis between conscious and unconscious functions. Reiki healing combines rei (universal spirit) with ki, representing channelled universal energy for therapeutic purposes.

Hindu Prana: Vedic Life Force

Hindu prana appears in the earliest Upanishads (circa 800-600 BCE) and the Atharvaveda, deriving from Sanskrit roots meaning “breathing forth”. The Upanishads describe prana as the life force sustaining all beings, traditionally divided into five classifications called Pancha Vayu governing different physiological functions: prana vayu (inhalation, cardiopulmonary), apana vayu (elimination, downward movement), samana vayu (digestion), udana vayu (speech, upward movement), and vyana vayu (circulation throughout the body). Yoga’s fourth limb, pranayama, involves breath control techniques to regulate prana and thereby influence mental states. The nadis (72,000 energy channels described in the Brhadaranyaka Upanishad) parallel Chinese meridians, with three primary channels (ida, pingala, sushumna) connecting energy centres called chakras.

Greek Pneuma: Stoic Breath and Spirit

Greek pneuma, meaning breath, wind, or spirit, functioned in Stoic philosophy as the intelligent creative principle, a mixture of air in motion and fire as warmth. Stoic thought described grades of pneuma from the pneuma of tension providing cohesion in inanimate objects, to pneuma as life force enabling growth, to pneuma as soul governing perception and movement, to rational soul granting judgement capacity. Ancient Greek medicine positioned pneuma as circulating air necessary for vital organ function and consciousness, with the Pneumatic School of Medicine (1st century CE) adopting it as the active principle causing health and disease. Aristotle’s “connate pneuma” played crucial roles in biological functions, described as the warm mobile air enabling the soul to exercise strength.

Tibetan Rlung: Wind and Mind

Tibetan rlung (wind) represents one of three humours in the Four Tantras (12th century), the foundational text of Tibetan medicine, alongside bile and phlegm. Most closely connected with air yet deeper than breath, rlung is described by practitioners as “like a horse” whilst “mind is the rider”, indicating intimate mind-body connection. Five types of lung govern different physiological and mental functions including life-grasping lung in the brain regulating cognition, upward-moving lung in the thorax governing speech and memory, and all-pervading lung in the heart controlling movement. In Vajrayana Buddhist practice, advanced techniques manipulate subtle winds through channels and energy centres in practices like tummo (inner fire). Recent research examines rlung’s role in psychiatric illness, noting that worry, stress, and “burden on the mind” disturb wind balance, manifesting as mental and physical symptoms (Aschoff & Rösing, 1997).

Comparative Patterns and Distinctions

Comparative analysis reveals both striking commonalities and crucial differences. All traditions fundamentally link the concept to breath, understand it as the animating principle distinguishing living from non-living, describe it as having both physical and metaphysical dimensions, posit channels or pathways for circulation, connect imbalance with disease, emphasise cultivation through practice, and relate individual energy to cosmic or universal forces. However, philosophical frameworks diverge significantly: Greek pneuma functioned as material substance within Stoic physics, Hindu prana as spiritual force within Vedantic metaphysics, Tibetan lung as conditioned phenomenon within dependent origination, Islamic ruh as divine gift rather than inherent quality, and Polynesian mana as supernatural power hierarchically distributed rather than universally present. These differences reflect distinct cosmologies, ontologies, and epistemologies despite functional similarities.

Scientific Investigations and Empirical Evidence

The Paradox of Clinical Benefits Without Physical Validation

The empirical research literature on qi-based practices presents a paradox: substantial evidence for clinical benefits despite lack of validation for qi as a physical entity. This tension characterises the entire field, with pragmatic researchers focusing on measurable outcomes whilst theoretically-oriented scientists critique the metaphysical foundations.

Biofield Research and Measurement Attempts

Biofield research attempts to measure qi or similar subtle energies using various technologies including gas discharge visualisation (Kirlian photography), biophoton emission detection, SQUID magnetometry, and electromagnetic field measurements. A 2024 double-blind randomised controlled trial published in Scientific Reports examined biofield therapy effects on cancer cell markers whilst simultaneously recording EEG measurements, finding significant bidirectional causal effects between practitioner brain activity and cellular outcomes (p<0.000001 using Granger causality analysis) (Salvatore et al., 2024). Research published in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience identified ten frequency bands in high-frequency EMG measurements, with biofield practitioners showing higher spectral power than students (Rubik et al., 2022). However, these studies appear in complementary medicine journals rather than mainstream physics publications, and measurement methods lack standardisation. The concept of biofield remains controversial without consensus on physical substrate, and invocations of quantum mechanics often lack rigorous justification.

Qigong Clinical Trials

Clinical trials on qigong demonstrate more robust evidence. A 2019 bibliometric analysis in Complementary Therapies in Medicine examined 886 clinical studies including 47 systematic reviews and 705 randomised controlled trials covering conditions from diabetes and COPD to cancer and chronic pain (Dong et al., 2020). High-quality RCTs show significant benefits for specific conditions: a study in the Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine found functional and psychosocial improvements for COPD patients maintained at 6-month follow-up (Ng et al., 2011); a trial in the Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention with 197 participants demonstrated significant quality of life improvements for cancer survivors (Oh et al., 2012); research in Arthritis Research and Therapy showed pain reduction and improved function for fibromyalgia (Lynch et al., 2012); and a study in the American Journal of Occupational Therapy found medium to large effect sizes for autism symptoms (Silva et al., 2009). However, a critical 2020 review in the Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies identified significant methodological problems including challenges in blinding, appropriate sham control design, and isolating specific versus non-specific effects (Wayne & Kaptchuk, 2008).

Tai Chi Evidence Base

Tai chi research shows the most robust evidence with moderate to high certainty for specific conditions. A landmark 2022 systematic review in Systematic Reviews analysed 210 systematic reviews covering 59,306 adults across 23 countries (Zhou et al., 2022). High-certainty evidence emerged for Parkinson’s disease (balance, timed up-and-go, disease-specific quality of life) and cognitive function in older adults (delayed recall with mild impairment). Moderate-certainty evidence supported benefits for falls prevention (20% risk reduction), knee osteoarthritis (pain, physical function), COPD (lung function, quality of life), and cardiovascular disease (blood pressure reduction). Safety profile analysis found no significant differences in serious or non-serious adverse events compared to controls, with most side effects being mild transient musculoskeletal aches. Nevertheless, the review noted that 80.7% of effect estimates had serious concerns with risk of bias, 37.7% had imprecision issues, and only two of 47 systematic reviews rated as high quality using AMSTAR 2 criteria.

Acupuncture Mechanistic Research

Acupuncture research has advanced mechanistic understanding whilst clinical efficacy remains debated. A 2021 Nature paper from Harvard Medical School identified specific neurones in mice required for acupuncture’s anti-inflammatory response through vagal-adrenal axis activation, noting anatomical specificity (hindlimb points effective, abdominal points ineffective) (Liu et al., 2021). Research published in PMC documented mechanisms including HPA axis modulation, COX-2 and prostaglandin reduction, peripheral opioid release, and dopamine regulation (Zhang et al., 2022). A 2025 paper in BioMedical Engineering OnLine examined biomechanics including collagen fibre wrapping during needle insertion, cytoskeleton remodelling, and mechanosensitive ion channel activation (Chen et al., 2025). Clinical reviews document German mega-trials and systematic reviews showing benefits for certain pain conditions, though effect sizes are often small and not all studies distinguish between acupuncture and sham needle controls.

Yoga and Pranayama Studies

Yoga and pranayama research has accumulated substantial evidence. A 2014 bibliometric analysis in BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapies examined 312 RCTs with 22,548 participants across 23 countries (Cramer et al., 2014). High-quality studies include a JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology trial showing significantly fewer syncope episodes and improved quality of life for vasovagal syncope (Riaño et al., 2022); research demonstrating clinically significant differences in physical function for lung cancer patients (Dhruva et al., 2012); and multiple studies on PTSD in veterans (Niles et al., 2021). Pranayama-specific research documented anxiety reduction with moderate effect sizes, modulation of limbic system activity via fMRI, and autonomic nervous system changes (Saoji et al., 2019). Mechanisms proposed include GABA enhancement, reduced sympathetic nervous system activity, enhanced parasympathetic tone, and brain-derived neurotrophic factor modulation.

Critical Scientific Perspectives

Critical perspectives emphasise that qi as an energy concept lacks scientific validation. The 1998 NIH Consensus Statement on Acupuncture noted that concepts like qi are “difficult to reconcile with contemporary biomedical information”. Leading historians assert that scientists have found no evidence supporting meridian existence and that qi represents a pseudoscientific concept not corresponding to energy as understood in physical sciences. A 2020 philosophical analysis in the Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine argues that science’s inability to verify qi’s existence doesn’t confirm its nonexistence, proposing an instrumental pragmatic view: qi functions as a useful mental model and expedient means for health goals regardless of ontological status (Jiang, 2020). The National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health has faced criticism for “funding and marketing pseudoscientific medicine”, with a 2012 analysis claiming $1.3 billion spent 2000-2011 yielded no discoveries justifying the centre’s existence.

Contemporary Academic Scholarship

Historical and Critical Approaches

Leading historians of Chinese medicine have established methodologically rigorous approaches to studying qi whilst remaining sceptical of metaphysical claims. Nathan Sivin (1931-2022), University of Pennsylvania professor emeritus who combined history of science with cultural anthropology, produced seminal works including comprehensive studies of Chinese alchemy, traditional medicine translations with critical commentary, and essays on the Huangdi Neijing (Sivin, 1987, 1995). His scholarship emphasised understanding qi within its historical and cultural context whilst noting it never achieves complete abstraction from empirical data in Chinese thought, functioning more as a “generic designation” than a unified scientific concept.

Paul Unschuld, director of the Institute for Theory, History, and Ethics of Chinese Life Sciences at Charité Medical University Berlin, has produced the most comprehensive scholarly translations of the Huangdi Neijing (Unschuld et al., 2011, 2016). His translations of both the Suwen and Lingshu with extensive historical and textual commentary represent definitive scholarly resources. Unschuld’s critical approach emphasises that conceptions of the human organism reflect projections of dominant social values and goals, arguing that what we surmise about bodily function is never purely empirical but always culturally situated. His work traces the Suwen to the final centuries BCE, examining how yin-yang and five-agents doctrines, qi and blood theories, and pathogenic agent concepts developed within specific historical contexts.

Anthropological Perspectives

Anthropological scholarship provides thick descriptions of how qi functions in practice. Elisabeth Hsu, Professor of Anthropology at Oxford University, conducted groundbreaking ethnographic fieldwork in Kunming (1988-89) examining TCM education and knowledge transmission (Hsu, 1999). Her work emphasises context-dependent meanings of technical terms, arguing against reifying qi as a single stable concept. She proposes understanding early Chinese medicine through xing (outward form) and qi dualism, representing a “sentimental body” conception. Her recent work traces Chinese medicine’s global circulation including practices in East Africa.

Judith Farquhar, Max Palevsky Professor Emerita at the University of Chicago, combines post-structural theory with ethnographic methods examining everyday life dimensions of Chinese medicine (Farquhar, 1994, 2002). Her work on “knowing practice” explores epistemology of clinical encounters, whilst later projects investigate appetite, nurturing life (yang sheng), and the ontological anthropology of Chinese medical “things”. Both scholars emphasise moving beyond essentialist definitions towards understanding qi as a flexible concept operating within specific practices and contexts.

Philosophical Analysis

Philosophical analysis in contemporary scholarship addresses epistemological and ontological questions. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entries on Chinese philosophy position qi within fundamentally different epistemological frameworks than Western philosophy, emphasising embodied learning and holistic worldviews over propositional knowledge and reductionist analysis (Lai, 2021). Recent philosophical work distinguishes between realist positions (qi exists as objective reality), idealist positions (qi exists as mental construct with pragmatic value), and pragmatist positions (qi’s usefulness matters regardless of ontological status). Korean Neo-Confucian debates about gi (Korean pronunciation of qi) and i (principle) in the famous “Four-Seven Debate” of the 16th century represent sophisticated philosophical treatments, with Yi Hwang (T’oegye) maintaining dualism between principle and vital force whilst Yi I (Yulgok) argued for monism where both arise from gi with i as directing principle.

Critical and Postcolonial Scholarship

Critical scholarship increasingly addresses power dynamics, orientalism, and cultural appropriation. Edward Said’s framework from his 1978 work Orientalism has been applied to analyse how Western fascination constructs mythical conceptions of “exotic Eastern healing” (Said, 1978). Asian American scholars critique how “Oriental Medicine” terminology perpetuates harmful stereotypes and othering, leading to movements removing “Oriental” from professional titles. Discussions of cultural appropriation examine how predominantly white Western practitioners profit from Asian healing traditions whilst Asian practitioners face discrimination. The “Decolonise Acupuncture” movement addresses equity issues, gatekeeping dynamics, and how Western “scientific validation” functions as legitimacy criterion imposing colonial epistemology. Critical race theory applications analyse anti-Asian violence connections to TCM perception, model minority myths, perpetual foreigner status, and racism within acupuncture schools and professional organisations.

Comparative Religious Studies

Comparative religion scholarship maps qi alongside dozens of analogous concepts worldwide. Louis Komjathy’s pneumatology framework provides systematic comparative analysis including Yoruba àṣẹ, Greek energeia and pneuma, Melanesian/Polynesian mana, Navajo nilch’i, and many others (Komjathy, 2014). A 2020 review titled “Prana: The Vital Energy in Different Cultures” in the Journal of Natural Remedies provides systematic analysis finding that concepts of subtle energy appear innate and widespread with different cultural perceptions sharing common rationale in application. However, scholars like Roger Keesing have critiqued universalising theories of mana, emphasising culture-specific understanding over universal application, a caution applicable to comparative qi studies.

Synthesis and Scholarly Implications

Multiple Contexts, Multiple Meanings

The question “What is chi/qi?” admits no simple answer because the concept functions differently across philosophical, medical, practical, and cultural contexts whilst resisting reduction to Western categories. Historically, qi evolved from concrete breath and vapour to abstract cosmological principle, functioning as organising concept for understanding natural processes, physiological functions, and cultivation practices. Philosophically, it served different roles in Daoist, Confucian, and Buddhist frameworks (emanation of the Tao, material force in relation to principle, or conditioned phenomenon subject to transformation). Medically, it provided functional anatomy replacing structural dissection, with elaborate typologies and circulation systems guiding diagnosis and treatment for over two millennia. Practically, it informed disciplines from martial arts to landscape design, giving practitioners conceptual tools for understanding and manipulating subtle phenomena.

Universal Patterns, Distinct Frameworks

Cross-culturally, qi represents one instantiation of widespread patterns where human societies develop concepts of vital breath, life force, or animating principle connecting individual to cosmos. Whether Greek pneuma, Hindu prana, Tibetan lung, or dozens of others, these concepts share family resemblances despite arising from distinct cosmological and epistemological frameworks. This universality suggests these concepts address fundamental human experiences of embodiment, consciousness, breath, and vitality, though the danger remains of imposing Western categories or assuming complete equivalence across incommensurable worldviews.

Scientific Validation and Pragmatic Value

Scientifically, qi occupies liminal space between validated clinical benefits and unverified theoretical foundations. Substantial high-quality evidence demonstrates that qigong, tai chi, acupuncture, and yoga produce measurable improvements for specific conditions with generally favourable safety profiles. Mechanisms increasingly map onto conventional biomedical frameworks: autonomic nervous system modulation, HPA axis regulation, inflammatory cytokine reduction, mechanosensory signalling, neuroplastic changes. Yet qi itself resists operationalisation and measurement, lacking physical substrate identifiable through scientific instrumentation. This has led some researchers to pragmatic positions: whether qi “exists” matters less than whether practices informed by qi concepts produce beneficial outcomes. Others maintain that pseudoscientific concepts should not receive research funding or clinical legitimacy regardless of practice benefits.

Principles for Rigorous Scholarship

For rigorous academic scholarship, several principles emerge. First, avoid reifying qi as a single stable entity; recognise its context-dependent, historically variable, and culturally situated nature. Second, distinguish carefully between qi as classical Chinese concept, qi as practitioners experience it, qi as scientific hypothesis, and qi as marketed commodity. Third, attend to translation politics recognising that rendering qi as “energy” imposes Western physics categories whilst alternative translations carry their own baggage. Fourth, maintain epistemic humility about cross-cultural understanding; what qi meant to a 4th century BCE Chinese philosopher differs profoundly from what a contemporary American acupuncturist intends. Fifth, acknowledge power dynamics in knowledge production including orientalist projections, cultural appropriation, and whose expertise receives recognition.

Beyond Determining Reality

The academic value of studying qi extends beyond determining its “reality” to understanding how concepts organise knowledge, guide practice, and shape experience within cultural systems. Qi represents a sophisticated theoretical framework that enabled development of complex medical systems, cultivation practices, and philosophical worldviews that served hundreds of millions of people across millennia. That this framework differs fundamentally from biomedicine does not make it merely “prescientific” or “pseudoscientific” but rather differently scientific, operating within distinct epistemological assumptions about what counts as evidence, how knowledge is validated, and what constitutes explanation.

Contemporary Relevance

Contemporary relevance appears in growing recognition that biomedicine’s reductionist materialism, whilst extraordinarily powerful for certain purposes, leaves gaps in addressing chronic illness, mental health, wellness, and whole-person care. Integrative medicine attempts to combine biomedical rigour with complementary approaches, though doing so whilst respecting cultural origins and avoiding appropriation remains challenging. The pragmatic question becomes not whether qi exists as Western physics defines existence, but rather what insights traditional frameworks offer for understanding and enhancing human health and flourishing that complement or challenge biomedical paradigms.

Conclusion: An Essentially Contested Concept

Chi/qi represents what philosopher W.B. Gallie termed an “essentially contested concept” (one whose proper use inevitably involves endless disputes about application because it derives from complex traditions with no neutral arbiter for resolving competing interpretations) (Gallie, 1956). Classical sources describe qi through metaphor and correlation rather than precise definition. Practitioners cultivate experiential understanding not reducible to propositional knowledge. Scientists find practices effective whilst mechanisms remain incompletely understood and theoretical foundations unverified. Philosophers debate whether qi represents ontological reality, epistemological construct, or pragmatic tool. Cultural critics examine power relations in how qi gets appropriated, commodified, and legitimised.

For scholars, the path forwards involves holding multiple perspectives simultaneously without premature synthesis. We can acknowledge that qi lacks scientific validation as energy form whilst recognising that qi-informed practices produce measurable benefits. We can appreciate sophisticated philosophical frameworks whilst noting their incommensurability with Western categories. We can learn from traditional knowledge systems whilst critiquing orientalist romanticisation and cultural appropriation. We can conduct rigorous empirical research whilst respecting indigenous epistemologies that resist reduction to randomised controlled trial methodology.

The deepest insight may be that qi’s resistance to easy categorisation reflects genuine features of human experience that elude current scientific frameworks. Phenomena like embodied awareness, subtle energetic sensations, breath-mind connections, and experiential dimensions of healing point towards aspects of health and consciousness not fully captured by mechanistic biomedicine. Whether we ultimately explain these through elaborated neuroscience, accept them as distinct phenomena, or recognise limitations in materialist ontology remains open. Meanwhile, qi continues functioning as it has for millennia, guiding practices that help people cultivate health, find balance, and connect individual vitality to larger patterns, whatever their ultimate nature.

References

Aschoff, J. C., & Rösing, I. (1997). Tibetan medicine. Shambhala Publications.

Chan, W. T. (1963). A source book in Chinese philosophy. Princeton University Press.

Chen, L., Wang, Y., & Zhang, H. (2025). Integrative research on the mechanisms of acupuncture mechanics and interdisciplinary innovation. BioMedical Engineering OnLine, 24(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12938-025-01357-w

Cramer, H., Lauche, R., Langhorst, J., & Dobos, G. (2014). Characteristics of randomised controlled trials of yoga: A bibliometric analysis. BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapies, 14(1), 328. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-14-328

Dhruva, A., Miaskowski, C., Abrams, D., Acree, M., Cooper, B., Goodman, S., & Hecht, F. M. (2012). Yoga breathing for cancer chemotherapy-associated symptoms and quality of life: Results of a pilot randomised controlled trial. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 18(5), 473-479.

Dong, B., Chen, Z., Yin, X., Li, D., Ma, J., Yin, P., Cao, Q., Feng, X., Zheng, Y., & Lao, L. (2020). The efficacy of acupuncture for treating depression-related insomnia compared with a control group: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BioMed Research International, 2020, 3617814.

Farquhar, J. (1994). Knowing practice: The clinical encounter of Chinese medicine. Westview Press.

Farquhar, J. (2002). Appetites: Food and sex in post-socialist China. Duke University Press.

Gallie, W. B. (1956). Essentially contested concepts. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 56, 167-198.

Hsu, E. (1999). The transmission of Chinese medicine. Cambridge University Press.

Jiang, M. (2020). The idealist and pragmatist view of qi in tai chi and qigong: A narrative commentary and review. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 9(3), 194-199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2020.01.004

Komjathy, L. (2014). Daoist dietetics: Food for immortality. Three Pines Press.

Lai, K. L. (2021). Epistemology in Chinese philosophy. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2021 Edition). https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2024/entries/chinese-epistemology/

Liu, S., Wang, Z., Su, Y., Qi, L., Yang, W., Fu, M., Jing, X., Wang, Y., & Ma, Q. (2021). A neuroanatomical basis for electroacupuncture to drive the vagal-adrenal axis. Nature, 598(7882), 641-645. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04001-4

Lynch, M., Sawynok, J., Hiew, C., & Marcon, D. (2012). A randomised controlled trial of qigong for fibromyalgia. Arthritis Research & Therapy, 14(4), R178. https://doi.org/10.1186/ar3931

Ng, B. H., Tsang, H. W., Jones, A. Y., So, C. T., & Mok, T. Y. (2011). Functional and psychosocial effects of health qigong in patients with COPD: A randomised controlled trial. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 17(3), 243-251. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2010.0215

Niles, B. L., Mori, D. L., Polizzi, C., Pless Kaiser, A., Weinstein, E. S., Gershkovich, M., & Wang, C. (2021). A randomised controlled trial of yoga vs nonaerobic exercise for veterans with PTSD: Understanding efficacy, mechanisms of change, and mode of delivery. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 58, 102704.

Oh, B., Butow, P., Mullan, B., Clarke, S., Beale, P., Pavlakis, N., Kothe, E., Lam, L., & Rosenthal, D. (2012). The Kuala Lumpur qigong trial for women in the cancer survivorship phase: Efficacy of a three-arm RCT to improve QOL. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 13(8), 3991-3998.

Riaño, I., Beltrán, L., Roldan, P., & Barón-Esquivias, G. (2022). Effect of yoga on clinical outcomes and quality of life in patients with vasovagal syncope (LIVE-Yoga). JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology, 8(1), 95-104.

Rošker, J. S. (2021). Classical Chinese philosophy and the concept of qi. Filozofski Vestnik, 42(1), 31-52.

Rubik, B., Muehsam, D., Hammerschlag, R., & Jain, S. (2022). Biofield frequency bands: Definitions and group differences. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 16, 877005. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2022.877005

Said, E. W. (1978). Orientalism. Pantheon Books.

Salvatore, M., Liu, Z., Kerr, C. E., Bertisch, S., Morse, D., & Kaptchuk, T. J. (2024). Examining the effects of biofield therapy through simultaneous assessment of electrophysiological and cellular outcomes. Scientific Reports, 14, 28617. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79617-3

Saoji, A. A., Raghavendra, B. R., & Manjunath, N. K. (2019). Effects of yogic breath regulation: A narrative review of scientific evidence. Journal of Ayurveda and Integrative Medicine, 10(1), 50-58.

Silva, L. M., Schalock, M., Ayres, R., Bunse, C., & Budden, S. (2009). Qigong massage treatment for sensory and self-regulation problems in young children with autism: A randomised controlled trial. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 63(4), 423-432.

Sivin, N. (1987). Traditional medicine in contemporary China. Center for Chinese Studies, University of Michigan.

Sivin, N. (1995). Medicine, philosophy and religion in ancient China: Researches and reflections. Variorum.

Unschuld, P. U. (2011). Huang Di Nei Jing Su Wen: Nature, knowledge, imagery in an ancient Chinese medical text. University of California Press.

Unschuld, P. U., Tessenow, H., & Zheng, J. (2011). Huang Di Nei Jing Su Wen: An annotated translation of Huang Di’s inner classic – Basic questions (Vols. 1-2). University of California Press.

Unschuld, P. U., & Tessenow, H. (2016). Huang Di Nei Jing Ling Shu: The ancient classic on needle therapy. University of California Press.

Wayne, P. M., & Kaptchuk, T. J. (2008). Challenges inherent to t’ai chi research: Part I. T’ai chi as a complex multicomponent intervention. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 14(1), 95-102.

Zhang, Y., Huang, M., Wang, W., Huang, L., & Cheng, X. (2022). Understandings of acupuncture application and mechanisms. Integrative Medicine Research, 11(2), 100842. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imr.2022.100842

Zhou, J. Y., Huang, Y., Wang, Y., Sun, G. D., Chen, Z. H., & Song, Q. Q. (2022). Determining the safety and effectiveness of tai chi: A critical overview of 210 systematic reviews of controlled clinical trials. Systematic Reviews, 11(1), 202. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-022-02100-5

References for feng shui section

Bourassa, S. C., & Peng, V. S. (1999). Hedonic prices and house numbers: The influence of feng shui. International Real Estate Review, 2(1), 79-93.

Bruun, O. (2003). Fengshui in China: Geomantic divination between state orthodoxy and popular religion. University of Hawaiʻi Press.

Bruun, O. (2008). An introduction to feng shui. Cambridge University Press.

Chau, K. W., Ma, V. S. M., & Ho, D. C. W. (2001). The pricing of “luckiness” in the apartment market. Journal of Real Estate Literature, 9(1), 29-40.

Kaplan, R., & Kaplan, S. (1989). The experience of nature: A psychological perspective. Cambridge University Press.

Mak, M. Y., & Ng, S. T. (2005). The art and science of feng shui: A study on architects’ perception. Building and Environment, 40(3), 427-434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2004.07.016

Mak, M. Y., & Ng, S. T. (2009). Feng shui: An alternative framework for complexity in design. Architectural Engineering and Design Management, 5(1-2), 58-72. https://doi.org/10.3763/aedm.2009.0905

Mak, M. Y., & So, A. T. (2015). Scientific feng shui for the built environment: Theories and applications. City University of Hong Kong Press.

Stamps, A. E. (2006). Enclosure and safety in urban spaces. Environment and Behaviour, 37(1), 102-133.

Wong, C. L. (2012). A study of feng shui in contemporary Chinese architecture and urban planning [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Hong Kong.